The Gangster Film Imposter Syndrome

- Vishnu Gupta

- Jan 7, 2019

- 5 min read

Updated: Jan 17, 2019

Last year marked the 20th anniversary of the release of Satya (Dir. Ram Gopal Varma). Satya is a unique and special film in the history of Bollywood for several reasons. Firstly, it spawned a whole new genre of films, the gangster film, which has resulted in some of the best works in Bollywood in the past couple of decades—Vaastav (Mahesh Manjrekar, 1999), Maqbool (Vishal Bhardwaj, 2003), and Johnny Gaddaar (Sriram Raghavan, 2007) to name a few. Secondly, Satya created humanization for the gangster, the scumbag, the drug-dealer—stereotypically villainous characters that were now the protagonists of the story—similar to what Pulp Fiction (Quentin Tarantino, 1994) did for such characters in Hollywood.

Gangs of Wasseypur (Anurag Kashyap, 2012) is the spiritual successor of Satya, both in style and success. For me, the film (while there were two films released theatrically I shall regard them as one as it was originally screened at film festivals) is truly special. For the first time, I saw that an Indian sensibility can be merged with global aesthetics, music can be used to make art and not money, and that the dark and comic can be juxtaposed without being jarring. This was the pretentious answer. Simply put, the film is just so fucking dope! All the actors kill as their characters, the score is immaculate, the cinematography and editing flow like a river, and the ending is one of the most cathartic I’ve seen in all of cinema. I would happily sacrifice my thumb like Sartaj Singh in Sacred Games (Vikramaditya Motwane, 2018) for the ability to watch the movie for the first time. The film is special not just for me, but seemingly all of India. The number of Faizal Khan memes on Instagram is a testament to this.

Last year’s Amazon Prime TV series Mirzapur (Karan Anshuman) felt like a amateurish student film retelling of Gangs. Gangs is a gold plated 9mm Beretta with a red dot and an extended clip while Mirzapur is a rusty desi katta (local gun) that’ll leave you with a lifelong handicap. The characters are drab, the cursing and violence is excessive and unnatural, and the writing is some of the cringiest I’ve seen in a while, and sounds exactly like what it is—an urbanite attempting to speak the language of people that live in an entirely different world. The entire sensibility is the projection of a city-dweller’s imagination of small town violent life. The show also looks like it was shot with DSLRs and lit only with two LEDs. Amazon, dude, the least you can do is give your creators a decent budget and crew. You can literally see the shadow of a crew member move in the very first shot of the show. Mazaak chal raha hai kya madarchod?! (Is this a joke to you motherfucker?!)

As bad as Mirzapur is, it is indicative of a recent obsession in Hindi cinema and television: the gang violence of second tier cities. As metros in India grow richer and closer to the first world, storytellers have turned to the smaller towns to explore narratives. What these gangster narratives do is not just explore but exploit. Many of the viewers remain in the larger cities and watch the gritty violence and abusive language from a convenient distance. The small town viewers have no say in what these representations are doing to India’s understandings of their towns. Whether they were ever approached for insight into the incidents is not known. In fact, even Wasseypur residents had issues with Gangs upon release. This representation makes the reputation of cities in U.P. and Bihar worse, and consequently the reputation of UPites and Biharis.

The growing anti-immigrant sentiment in metropolitan cities and increasing violence against minorities, fueled by major political parties, is only exacerbated by poor representation of such communities in our films and television shows. The lofty elites simply push their noses higher and look the other way, failing to recognize that the mansion they live in could not have been built without the support of the migrant working class. As filmmakers, we have a greater responsibility to understand the impact of our narratives. We should know not to create stories about themes and cities that we have little knowledge of or have spent little or no time in. When representing communities outside of those usually portrayed in the mainstream, we need to approach narratives with the level of complexity and nuance expected of an academic. The social ramifications of representations greatly outweigh gold coins in pockets.

Gangster narratives that are distributed through streaming services also fall prey to overindulgence of violence and abusive language. It’s one thing to want to represent reality, but another to take things to the extreme for the sake of shock. It’s the cinematic equivalent of the reign of terror following noble ambitions of establishing freedom. Over time, a balance shall be found but right now, the policy is one of the guillotine. Many gangster tales invariably end up glorifying violence and romanticizing the lifestyle. The creators of such content fail to remember that the best gangster narratives showcase the brutality and cruelty of the lifestyle without ascribing any positive or negative sentiments towards it. This leaves the audience to decide whether what they’ve seen is moral and justified, and most are usually horrified by the images, which affirms my faith in humanity a bit.

The problem is that many are trying to recreate Gangs, or at least appropriate it heavily. The simple fact of the matter is, there cannot be a better Gangs type story than Gangs. If Satya is analogous to The Godfather (Francis Ford Coppola, 1972), then Gangs of Wasseypur is analogous to Goodfellas (Martin Scorsese, 1990). The first provided the blueprint, and the second perfected it. All successful gangster films that have followed Goodfellas found ways to both draw inspiration from the films that came before, yet distinguish themselves by placing the story in a different context and narrative. Imagine if someone tried to recreate the horror of Psycho (Alfred Hitchcock, 1960). Actually, they did—Psycho (Gus Van Sant, 1998)—and it was terrible and absolutely pointless. One should go to Gangs of Wasseypur as a horror director goes to Psycho or a space director goes to 2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick, 1960), for a source of inspiration but never for a source of material.

The Hindi gangster films and series that have followed Gangs have lacked in originality and nuance. Babumoshai Bandookbaaz (Kushan Nandy, 2017), Daddy (Ashim Ahluwalia, 2017), Mirzapur, just to name a few, have been flimsy, superficial, and derivative. They are pure exploitation cinema—gangsploitation at its worst. Pulp fiction at best.

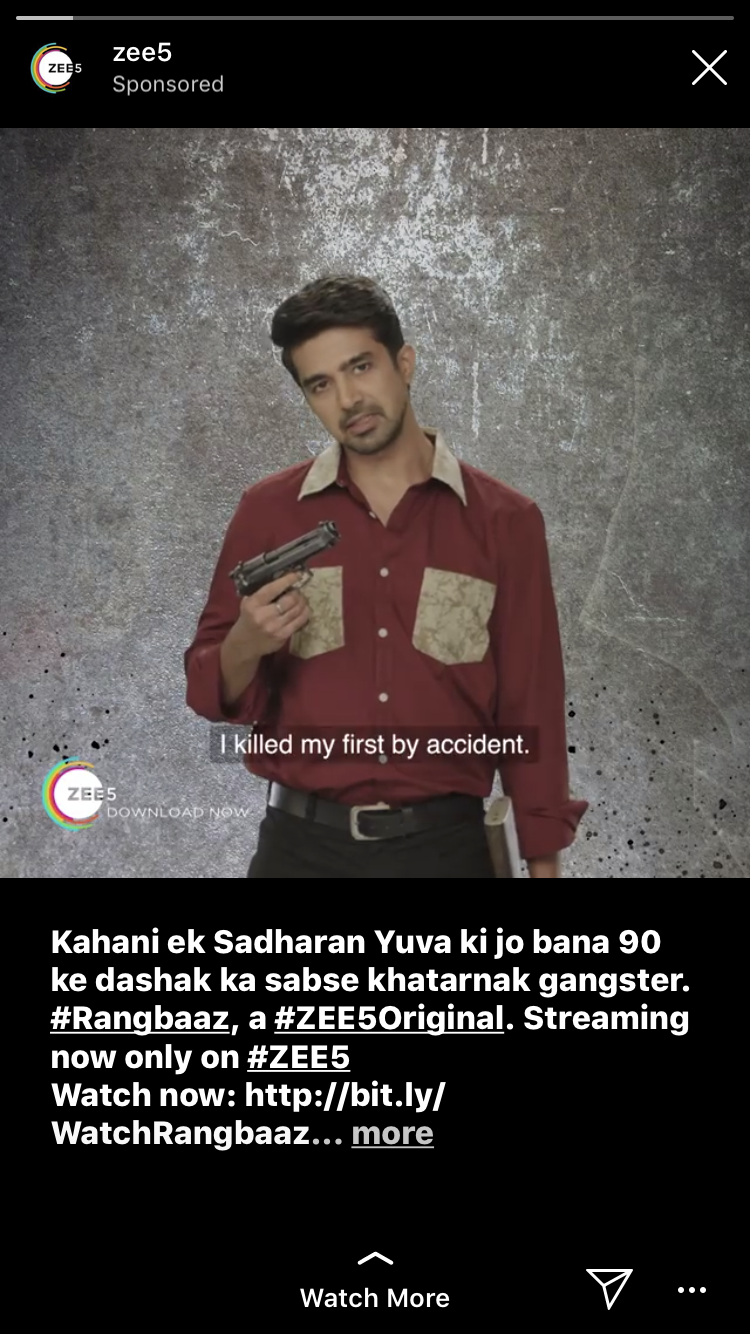

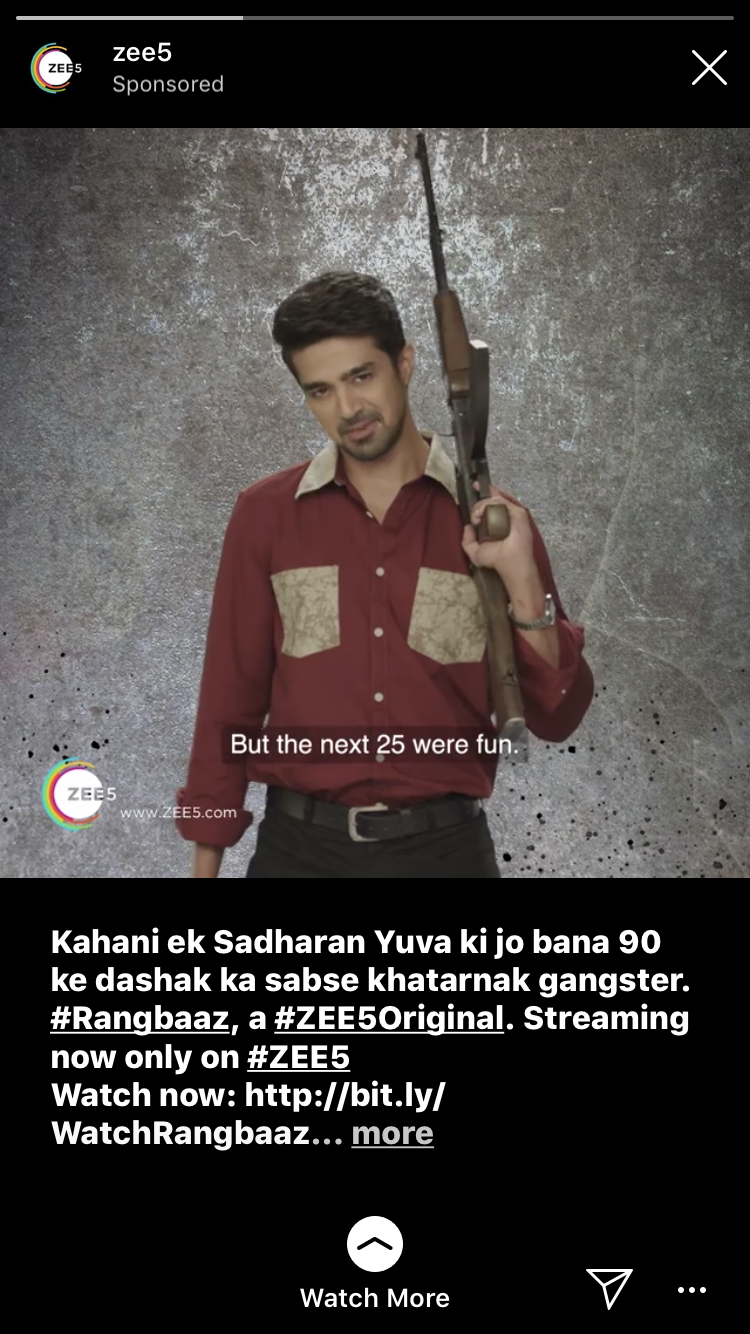

And if I’m getting ads like this on my Instagram, this new obsession doesn’t seem like it will die down soon.

Bollywood has a habit of beating a dead horse, much like Faizal Khan at the end of Gangs, resulting in its/their own demise. Bollywood is the equivalent of your grandmother feeding you halwa (pudding). The first few bites are amazing, but then she feeds you until you’re comatose. Someone needs to teach Bollywood and my grandmother about diminishing marginal utility.

Commentaires